NAPIRZE

“The great historic barrier of the Caucasus Mountains rises up across the wide isthmus separating the Black and Caspian seas in the region where Europe and Asia converge.”[1]

For centuries, the melting snow from these mountains has molded the physical and cultural landscape of the region. While every city and settlement in Georgia has historically thrived on the resources provided by its rivers, the modern era has seen a significant shift in the role of waters for contemporary society.

Presently, the majority of Georgia’s population resides in proximity to rivers, with up to two million people inhabiting the Mtkvari River basin. Originating in Turkey, the Mtkvari River spans a total length of 1515 km, with ~331 km passing through Georgia draining up to twelve thousand major and minor tributaries before flowing into Azerbaijan and ultimately reaching the Caspian Sea.

Despite the vital role Mtkvari played in establishment of these cities and settlements, the advent of the industrial age resulted in a decline in mankind’s ability to analyze the functional benefits of the water that led to the disappearance of the river culture.

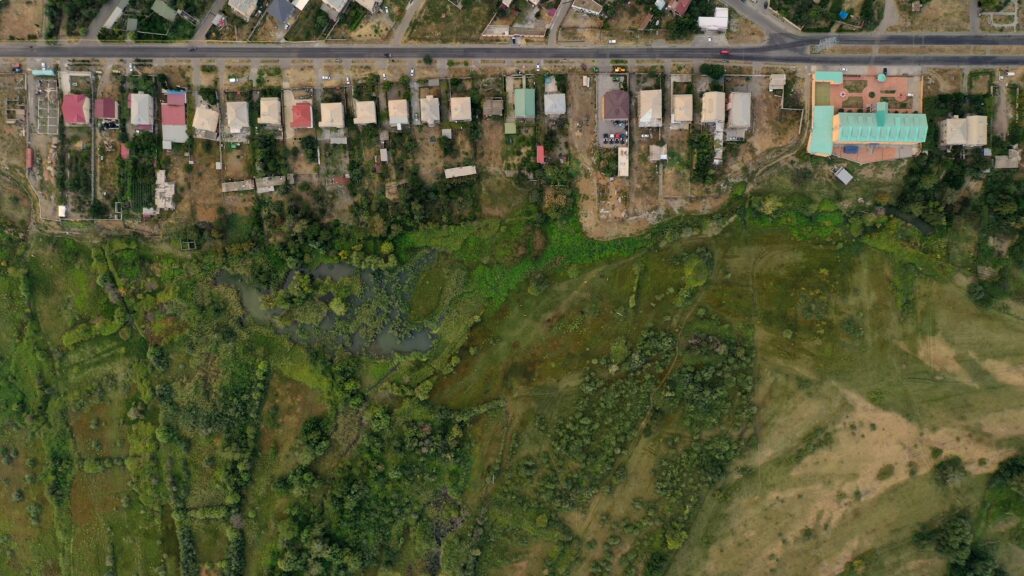

In an effort to address this circumstance, we initiated a project with the objective of rejuvenating the connection between humanity and the river. Community-led restoration project began in the Rustavi’s floodplain, situated at the city’s core, easily accessible from any point in Rustavi within a brief timeframe. Regrettably, during the 1990s, social and economic challenges led to the deforestation of the floodplain, resulting in the destruction of local biodiversity. Despite the present abandonment of the area and considerable disruption to the ecosystem, distinctive landscape and urban planning in this location uniquely enable us to execute the project.

One of our most cherished aspirations is to re-attract otters (Lutra lutra meridionalis). They were native to this region but have disappeared due to habitat destruction. Their presence will serve as a remarkable indicator of our success and demonstrate a huge ecological achievement.

As of now, 133 bird species have been documented in the floodplain, suggesting that, despite the damage, the area possesses potential for regeneration and transformation into a natural area within the urban landscape. Our objective is to attain and subsequently sustain this transformation. In the initial phase of restoring biodiversity, our plan involves reforesting the area and assist natural regeneration.

Addressing water and soil pollution poses a significant challenge for the project due to its resource-intensive nature. Given that the area is abandoned, with only a small portion enclosed by fencing, residents frequently dispose of construction waste, a primary contributor to soil pollution. Moreover, the lack of a fence has led to seasonal grazing, hindering the regeneration process. The river faces contamination from illicitly connected sewage systems and household waste. It must be noted that water extracted from the northern dam in the floodplain irrigates up to 15,000 hectares of agricultural land in Georgia and fills up Jandara reservoir. Mtkvari river is staying main source of drinking water for 70% of population of Azerbaijan, including the main cities – Baku, Ganja and Sumgait

“The South Caucasus countries are faced with water quantity and quality problems. In general terms, Georgia has a lot of water, Armenia has some shortages due to poor management, and Azerbaijan has a lack of water; moreover, its groundwater is of poor quality. In Georgia, the main use of the Kura–Araks water is agriculture. In Armenia it is agriculture and industry whereas in Georgia drinking water is withdrawn from a large fresh groundwater stock. In Azerbaijan, the Kura–Araks water is the primary source of freshwater, and 70 percent of drinking water comes from these rivers. In general, water is used for municipal, industrial, irrigation, fishery, recreation, and transportation purposes. The main water use is agriculture, followed by industry and households uses (Berrin and Campana, 2008).” [2]

At first glance, the floodplain’s both banks seem easily reachable to the public because of its location. However, the absence of a trail system across the 300-hectare area complicates movement within the floodplain. Furthermore, the lack of protection in the area poses challenges in monitoring and controlling issues such as poaching and pollution.

To address the mentioned challenges, we have dedicated several years to research the Rustavi floodplain. This comprehensive investigation includes an exploration of its landscape history, the application of the Miyawaki method for afforestation, studies on restoration examples, the analysis of native vegetation, insights into the river cycle, planning trail network and more. Simultaneously, our efforts are focused on securing the essential resources for project implementation. To enhance awareness about the floodplain, we utilize the urban garden (NAPIRZE HQ), which, for the second consecutive year, has welcomed pupils, students, and like-minded individuals from various corners of the world, who share an interest in exploring the cultural landscape of Rustavi.

We are currently gearing up for spring 2024, during which we will start the initial afforestation process. Additionally, we will continue developing the trail network and kick off a crowdfunding campaign to support the installation of information boards and signs in the floodplain.

See you on the field!

References

- [1] Britanica – https://www.britannica.com/place/Caucasus

- [2] Transboundary River Basins – Kura Araks River Basin. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2009

- [3] Bird photos by Kakha Gogolashvili